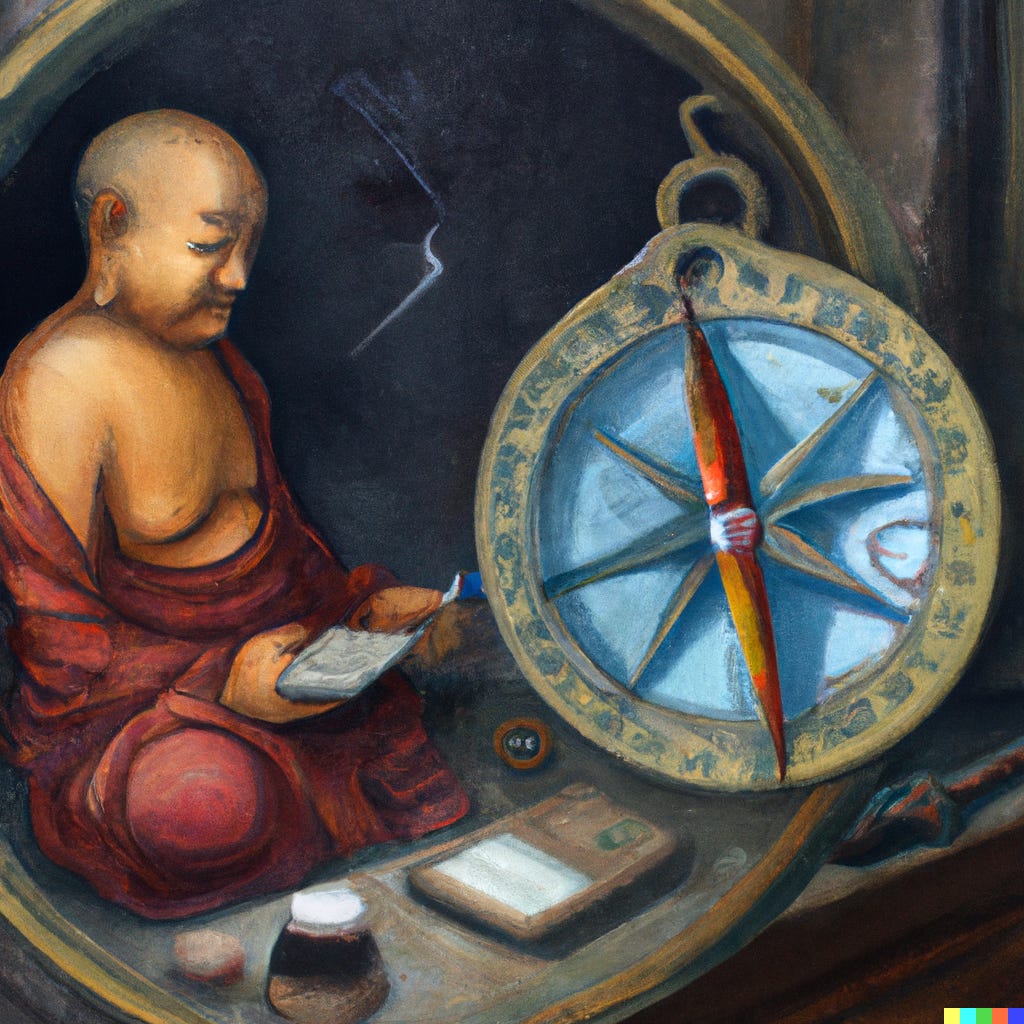

Cartography and Inner Development

Trying to find language to adequately describe human development is not an easy task. Each human being, as well as the environment in which they are embedded, are so unique and complex that models and simplifications always seem to miss something essential.

That does not mean, however, that the language and models to better understand it are impossible to find or create. It just means that we are at a very early (even infantile) stage of our understanding of, and language for, human development.

Within Life Itself, the language we like to use comes from a Buddhist metaphor of ‘maps and rafts', as outlined in this post here. Within our group, we have found it useful to expand on this metaphor using more cartographic terms. In this language, 'maps' refer to models of human development; 'domains' refer to specific domain of human development; ‘locations’ refer to specific spots on the map; and ‘rafts’ refer to specific practices which help one to get to different locations. Within this post, we will build on this metaphor by discussing the importance of 'features'.

Features

While there is much work and discussion to be had for clarifying and developing this language, a recent discussion within our research group highlighted the importance of 'features'. A 'feature' of a map refers (unsurprisingly) to a specific 'feature'- or quality, or state in that map. The metaphor makes more sense when one considers it as a process: if, for example, one is travelling across a certain region and spots a certain species of tree (which is not common in another area) this 'feature' signifies that one is a new location, or region.

The same might be said about human development. If the domain is agency, then certain features might be said to suggest that one is at certain location on a map, based on different features- determining ones routine, or taking responsibility for ones actions, might be features of the domain of agency. While these features might vary depending on the different domain one is discussing, features can be a good way of pointing to a specific location or region on a map. Indeed, we might even go on to say that it is through features that maps are made.

Alchemists and Early Navigators

‘Features’, then, can be a meaningful way of better describing the complexity of human development within this ongoing metaphor of cartography and human development, which is still evolving. We might even say that the situation we are currently in- studying human development and trying to find an accurate language for it- is not so different from early cartographers- as map makers who paved the way for modern navigation. Indeed, many 'maps' have been made of human development, and all of them are of a specific area or terrain: ego development, stages of faith, or levels of complexity are, for instance, some examples that many people are familiar with. Crucially, early maps, before being integrated into a more holistic atlas, existed as regions of the World, and through comparing and integrating many different maps, more detailed and complete atlases were eventually made, which allowed for a more complete picture of the terrain of the World.

It is also worth pointing out that before more detailed and complex maps were made, features were also what inspired and helped guide early navigators. One of our inspirations in our ongoing dialogue has been early Polynesian sea navigation, which was possible through advanced, almost supernatural, sensemaking of certain features. By looking at the stars, the patterns of birds, the waves of the ocean, and other, seemingly mundane things, early Polynesian navigators were able to wayfind across the pacific with masterful skill- at least for their time.

Along with early cartographers and navigators, we might also position our current context as similar to 'alchemists' in the medieval era, who were the forerunners of chemistry. Before chemistry was made into a more unified and complete science with a coherent language, alchemists experimented to the best of their ability with what they had and what they knew, and their learnings eventually paved the way for chemistry to emerge. As alchemists were concerned with the transformation of matter, we might say that those who study and pioneer human development are more concerned with the transformation of inner life- or 'consciousness'.

Even though ‘inner life’ seems inherently more complex and mysterious than metals and geographic terrain, those who are looking for language to describe the complexity of this development are not all that different from alchemists, or early cartographers, or navigators. We are in mostly uncharted regions, but making useful maps; we are looking at transformation, but not exactly sure how it works, or what an accurate language might look like. Indeed, we might be inclined to look into these earlier disciplines and draw on key lessons. While there might be many, we might be reminded of a well known one from alchemy: nothing can be magically turned into gold.