Getting Over Our Allergy to Religion

Religion plays an important role in any effort to make a radically wiser, weller world. However, today there is widespread allergy to religion, at least in the West. Is there a way forward?

From the early days of Life Itself, we’ve had a strong sense that ‘religion’ plays an important role in any efforts to make a “radically wiser, weller world” and a second renaissance. This is true both at the broader movement and ecosystem level, as well as at the level of individual organizations like Life Itself.

However, we also live in a world, at least in the west, which has a very strong allergy to religion. So much so, that it is often difficult or impossible to talk about religion — at best, we fall back to half-euphemisms like spirituality; at worst we avoid it altogether.

Nevertheless, it seems crucial to look at this topic given its importance. And it is a topic people are starting to talk about, see for example Wilber's Religion of Tomorrow or Vervaeke talking about the religion that is not a religion.

So in this essay we explicitly broach the topic of religion and look at:

Why care about religion? Why is it important?

What do we mean by religion?

What would religions of the future look like? Are there key common principles?

What kind of concerns would people have and how would they be addressed?

NOTE: this piece was originally published in March 2021 on Life Itself blog

Introduction: Our allergy to religion

We (i.e. secular westerners) have an allergy to religion because:

We think of religion as large institutional entities, primarily coming from a mythic-oriented judaeo-christian tradition

That type of religion has been on the wrong side of a metaphysical and epistemological argument with science

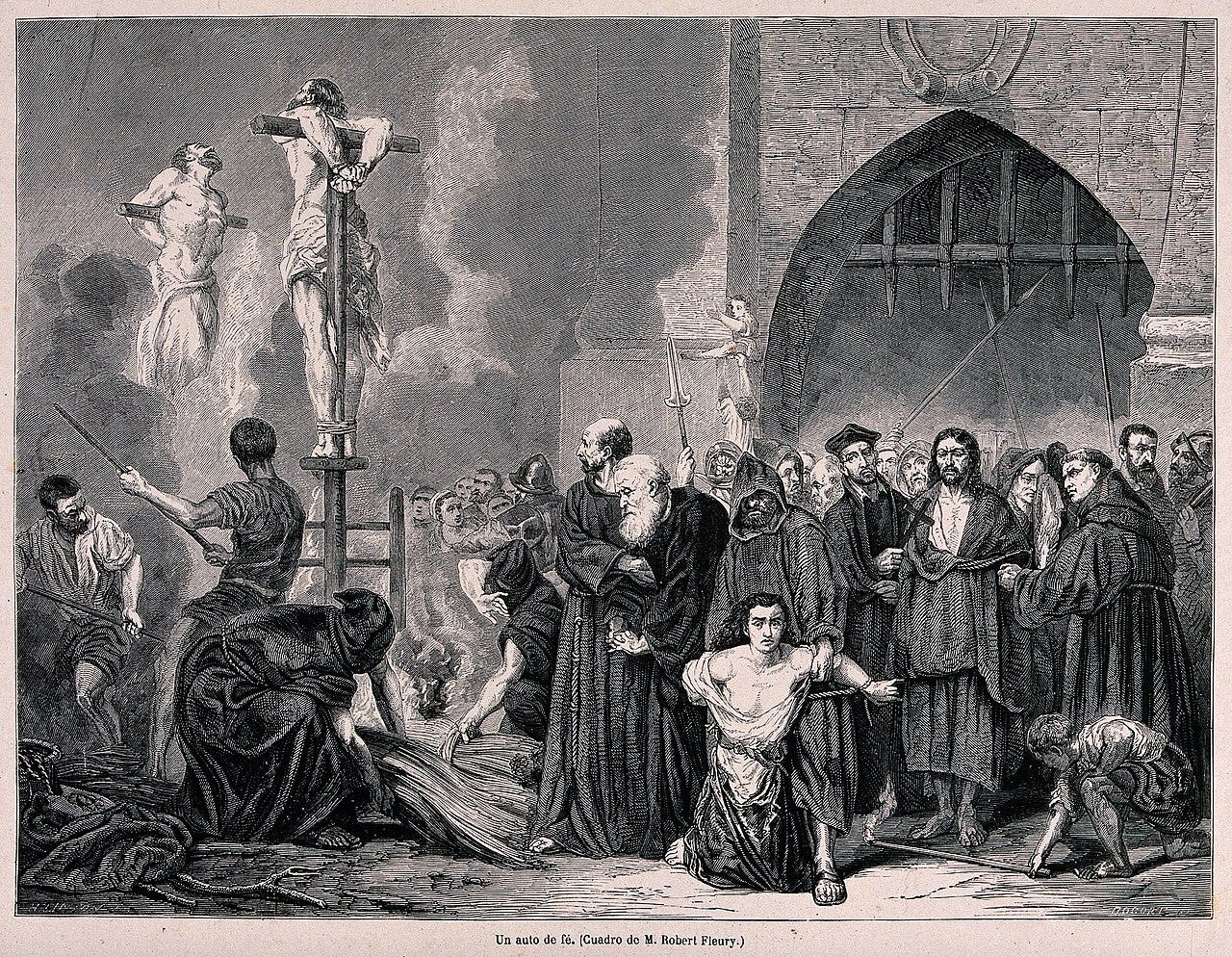

That type of religion was explicitly engaged in oppression and discrimination for a long time and especially during early modernity (e.g. Pope vs Galileo, the Inquisition etc)

Today those traditions have either become so watered down as to have little inspirational power, or, have reverted to fundamentalism which seems anti-progress in key ways (from the climate crisis to evolution)

Personally, I have an allergy because my early encounters with religion as a child were in the form of enforced Christianity at school. For me, this associated religion with force – being made to listen and do something every day at school even though I didn't believe it; and with intellectual coercion in being asked to believe in what seemed like blatantly false or unlikely claims like Moses and burning bush, or Jesus walking water.

However, part of the issue here is the definition of religion. It isn't just a relativising platitude to say that "science is a religion". Any paradigmatic way for making sense of the world ("sense-making") will ultimately have strong aspects of supra-rational belief. For example, those who are strong on science tend to assume that it can ultimately answer all questions including ones like "what is consciousness", "what is matter really made of" etc, or to ignore or exclude certain questions as irrelevant because not answerable e.g. "where did the universe come from", "what is the the purpose of life".

Indeed, the scientific approach becomes least attractive when it becomes fundamentalist, when it turns to scientism and reductionism – when awe is reduced to the firing of neurons.

If we accept this point, we see that:

Most of us who actually do have a religion or quasi-religion even if we don't think we have one

Having a religion is almost inevitable to any kind of functioning human collective.

Thus, the question to ask is "what kind of religion do we want" rather than "do we want a religion or not".

What is religion and what do they provide?

To build on the previous points, let's look in a bit more detail at what a religion consists of and what they provide. Roughly, religions provide something like the following:

An ontological and epistemological framework for establishing what exists, its nature and how we discover knowledge about it

An ethical framework about what we value and how we should behave

A set of psycho-technologies for practising/discovering those (ie. ontology and ethics) and cultivating wisdom and spiritual growth including a language/ grammar for these things.

(more implicit) A set of social technologies for organizing groups and society

A community of practitioners based on these

The root of religion is "religio" which means to bind together. The first two items provide a common belief (sense-making) system whilst the latter one provides an explicit community grounded in these.

The psycho-technologies are often less directly relevant for the religio aspect (and may not be used that much by the majority of participants). However, perhaps could make a strong case that these are important to key participants e.g. leaders where these can ensure higher quality leadership.

What's the problem with religion?

Religions becomes problematic when they become dogmatic and/or fanatic

The key flaw in most religions is that at some point they become dogmatic, righteous, calcified and stuck. Specifically, they make ontological claims, especially metaphysical ones, that aren't subject to revision or evolution and because of that commitment ended up feeling threatened by developments that undermine these (e.g. from science). They then end up as reactionary or irrelevant.

What this suggests is there are possibly (a few) key meta-features that make a religion more "problematic" vs "positive" (non-problematic).

We can immediately identify one such meta-feature from what we just said: closedness/openness. Closed looks like"we have the truth and it doesn't change". Open looks like "we are committed to these ideas but not attached to them, they are subject to revision in the light of experience".

A second meta-feature is whether the religion legitimises the use of force to impose its views on other groups – and not just physical force but e.g. social compulsion. It is this secondary implication which makes "religion" most obviously problematic for many "secular" people. This feature is also connected to the first meta-feature: the more certain and dogmatic one is about one's beliefs the more willing to use force. It is also obviously more directly linked to (negative) impact in the world.

Often, because of our past, religious is directly used as a synonym for dogmatic as in "I'm not going to be religious about my view X". And it is what we mean in the (negative) sense when we say something like "science has become a religion" i.e. it has become dogmatic and narrow-minded.

But it seems clear that not all the religions we call religions today are like this e.g. Zen Buddhism, Taoism, Quakers etc. Moreover, it certainly seems possible that we could have religions that were undogmatic.

Dogmatism, Relativism and Commitment

Some may argue that dogmatism is essential [to a religion], in that the opposite of dogmatism would be a weak relativism e.g. "I personally believe X,Y,Z but you can believe anything you want and what I believe is no more valid than what you believe and vice-versa".

I think this is confusing commitment with attachment. I can be committed to the belief of X,Y,Z and that it is universally true(r) – that is true for you as well as me and true(r) in the sense of being more true than anything else around at the moment.

However, I need not be attached to it: I can be open to the possibility of it being superseded or amended etc. In fact, if it is belief articulated in language, then it is necessarily only an approximation of any "truth" and hence always subject to revision and qualification.

Religions of tomorrow: what would they look like?

So what are key features of any religion of tomorrow aka "religion that is not a religion", a "secular religion", a "teal religion"?

Before coming to any specific suggestion for the form of a religion of tomorrow, let us first ask if there are general features or principles that should be present in any religion of tomorrow?

We can start by asking how we could identify these key features? One answer is derived from the previous section: if we can identify problematic features in existing religions, then we can invert that feature. For example, if dogmatism is problematic then we can hypothesize that anti-dogmatism i.e. "openness" may be important.

We can also identify the positive features of existing religions and select those. For example, most religions do involve clear, strong beliefs about ethics or even the nature of reality. We could term this "positivism" as opposed to relativism. This clarity and commitment of positivism seems important.

Distinguishing commitment from attachment and dogmatism from positivism

Of course, as just discussed, this commitment can become a problematic attachment or dogmatism. However, it seems essential – though not easy – to distinguish commitment from attachment and dogmatism. If not, we risk throwing out the baby with the bathwater ie. discarding commitment to avoid attachment. This would be as limiting as saying: I got hurt in my last relationship so I'm never going on a date again.

And worse follows: we cannot live in the world without some kind of normative commitments (ontological, ethical etc) – we need some assumed views to make sense of reality, to operate in the world, to communicate with others. Thus, trying to live without any commitment to a worldview is, in fact, impossible.

Nevertheless, we can pretend we don't have a worldview – that we don't have a “religion”. But then we end up in a position where we have a worldview but it is hidden from us – and so all the more problematic. It like an analogy of psychological suppression where my resentment to my father is still there shaping my life but utterly hidden from my view.

And this is often what has happened in modernity: we claim we are not religious but in fact we have turned science or technology or marxism into a religion.

To reiterate: in some important sense, we end up committed to a worldview aka “religion” whether we like it or not. Denying this leads to repression not a lack of a religion.

On post-modernism: the ultimate denial of having a worldview (when in fact you do)

A final aside regarding post-modernism. Post-modernism takes the suppression to its logical extreme.

This is something of the trap that post-modernism falls into as it becomes "religious" (in the bad sense of being dogmatic).

It became so obsessed with denying attachment to any particular worldview that it becomes attached and dogmatic about that very worldview (i.e. that no worldview is better than any other worldview). This is the performative contradiction of post-modernism made famous by Habermas (and Wilber).

Post-modernism is an important example because in many ways it appears "anti-religious" in the traditional conception of religion. It shows how it is even possible to be a dogmatic relativist – positions that at first glance seem to be fundamentally in opposition. But dogmatism can end up concealed inside of an anti-dogmatism. As such, it illustrates the trap that secularism can fall into. This is a first point.

And there is a second point beyond the concealed dogmatism. Post-modernism elevates lack of commitment into something desirable. It makes criticism cool and belief (commitment) at best naive and at worst oppressive. But what kind of world – and especially what kind of society – can you create from such a stance? A very weak and dissatisfying one. To be strong individually and collectively we need the strength of commitment. This can be hard to acknowledge because we have become so allergic to strength because it so often become attachment and force.

We need to re-understand strength: we have come to think it means the rigid, brittleness of iron or glass but instead we should think of the flexible strength of bamboo or oak.

Aside: Is there a contradiction in the last two points? If post-modernism is a religion doesn't that mean it provides the benefits you described including commitment. The answer to that is … yes to some extent it is. Post-modernism does create a collective to an extent, think of woke-ism or social justice warriors. But it is a relatively weak collective. Amongst other things, it has an allergy to leadership which makes it, well, hard to lead. It prioritizes deconstruction and criticism over construction and creation etc. All of these make it hard to inspire, build and lead.

General meta-features of the religions of tomorrow

Having got all of that out of the way, here is a list of some of the key general features – or "meta-features" – of religions of tomorrow:

Openness / Anti-fundamentalist / Evolutionary: claims are the truth or true(r) and they must be constantly examined in the light of your own and others experience and we must continue to evolve them

Pragmatic: do what works …

Positivist (anti-relativist): at the same time any religion would make explicit ontological claims (what is being etc), normative claims (about what is "better") and epistemological claims (what is knowledge). However, at per previous point, these are not absolutes. There is an up but not a top. Truth is a mountain with no top.

Supra-rational: the most core phenomenological / experiential truths are not describable in language though they may be pointable to.

And yet respecting reason and science

For this to work and not descend into relativistic individualism (my crystals are as valid as your meditation etc) you need a rigorous system for validating "expertise" (who is the Zen master). To avoid corruption this should be largely decoupled from any social power.

Explicit: religions should be explicit about being religions and their associated ontological, normative and epistemological claims.

Commitment to non-violence: an explicit commitment never to use force to enforce their beliefs.

Specific Beliefs of Religions of Tomorrow

Here are examples of some specific beliefs that could be part of a "religion of tomorrow":

Inner growth/evolution is possible and important. In fact, the growth that matters is not material growth but ontological growth, that is growth in our being and consciousness

Inner, ontological growth is potentially limitless: growth is possible as an adult and there is no apparent limit to this growth, at least on important dimensions like our worldview.

Growth is multidimensional encompassing (at least) spiritual, emotional, cultural and worldview dimensions.

More than matter, more than mind: we have a body, we have a mind. We interact in a world of matter and mind. And yet we are more than body and mind: we know this because there is an awareness of thought, of sensation. We experience and do not simply react to the sunset, the flower, the rain, or an insight. We experience redness and so on. There is seeing even if no "me" that sees. There is hearing even if there is no "me" that hears.

Interbeing: Forms and processes over essences (non-self etc). We tend to essentialize ourselves and the world. We create "I"s and things. With these things come separation and error. Just ask yourself: if there is an essential "I" when did it begin? Who were you before your parents were born? Strictly, interbeing is this point plus a kind of ethical stance of recognizing, realizing and acting from our awareness of interwoven-ness with the whole universe.

Signlessness: concepts (in language or in our mind) aren't real, they are only approximate labels for the mystery of manifesting reality. yet we constantly forget this. Good and bad don't exist. Black and White people don't exist. At least, not outside of our language and concepts.

Immanent transcendence: transcendence is possible. And it is possible in the here and now.

"We" are of the nature to die: There is no immortal "personal" soul, no permanent essence of our ego-minds. Like any other form, our ego-minds will dissolve. Remember the five remembrances.

Conclusion

It's time to heal our allergy to religion. After all, we have a religion whether we acknowledge it or not – to live and act in the world is to act from some basic commitments to the nature of reality, a sense of the good etc.

What's important is what kind of religions we choose. Here we have set out some key meta-features like openness and non-fanaticism as well as some examples of specific beliefs that may be included.

Ultimately there are going to be religions "religions of tomorrow" plural. They will likely include evolutionary versions of mainstream religions today as well as entirely novel forms (or radical revisions of mainstream versions).

Lastly, as per the appendix below, religions play a key, foundational role in deep social transformation – the transformation needed for a radically wiser, weller world to be possible.

Appendix: Religion and social transformation

Social transformation requires community and deep intention because …

Real community is essential to personal and social transformation

Deep Intention is essential to real community (and to social transformation)

Religion provides the bedrock for real community and deep intention

that which would underpin real community would look and feel like a religion

that which would ground personal transformation would look and feel like a religion

that which underpins deep intention would look and feel like a religion

⟹ religion is essential to deep social transformation

What is social transformation? Social transformation is more than social change, it is a "phase shift" in how we operate at multiple levels: economically, socially and culturally.

What is deep intention? Deep intention is intention that is "ontologically grounded", ie. where the intention is connected back to one's deepest beliefs and commitments.

For example, suppose I say my intention is "I want to do good in society" or "I want to help ex-addicts recover". Those purposes are great but not ontologically grounded.

To see this, suppose you were to ask me "why do you want to help ex-addicts recover or do good in society?" Then you get deeper answer. For example, I might say: "Because I believe this is part of serving Christ", or I may say: "This is acting out my Buddha nature and commitment to the Dharma".

Or suppose I say my "my intention is to help find intelligent life on other planets". You ask why and I then say: "Because I think exploration and discovery are fundamental to our nature and finding other life would show we are not alone".

These latter statements are more deeply grounded in my beliefs about the nature of the world and my purpose in it.

I really like this, thank you Rufus and Sylvie. May this awareness blossom! 🙏🪷🌈

Felt like an arrow shot in the right direction